Documenting design, Dan Brown

In his Spoolcast interview Dan Brown provides some interesting perspectives on documentation and design deliverables, using his book Communicating Design as a starting point.

Growing documents

Brown begins by suggesting that designers start documents with a basic nucleus of necessary information then adding detail in layers. He also put forward the idea that ideal documentation should be able to give a bird's eye view and address the road-level details that developers and quality analysts need.

It seems to me that multiple documents become the best approach to meeting this ideal of providing the bird's eye view and road level detail. In past work I've tended to use site maps or high level flow diagrams to give the high level information then use wireframes or lo-fi prototypes to get into the road level detail. (There is also need for technical documentation of both bird's eye and road level detail but these tend to fall to the Front End and Back End team leads.)

Concept models

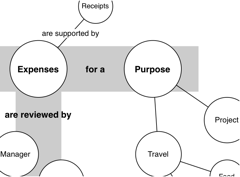

A concept model shows the relationships between the important elements of a web site and provides some initial planning outputs so we can work out what the key elements and key moving pieces are.

The key thing is that it doesn't box you into a specific approach of how to show the information. You're not locked into pages or actors. You have the flexibility to represent a specific page or a specific person, but there aren't rigid rules driving the diagram... the idea is to give the big picture as something to start with. As you move forward documenting it serves as a jumping point to move from into more detailed things like flow diagrams and wireframes.

The concept model paints the relationships between things... it's a learning tool.

Building this deliverable pushes you to learn about how all the concepts fit together and the resulting deliverable serves as a point of reference for you and teaching tool for communicating the relationships between the concepts to others.

Looking over a current project that's late in the requirements gathering stages it appears to me that starting from a concept map may have helped to better communicate our understanding of the system with the client and provide easier access to some of the high level information they wanted to share with the higher ups without getting mired in the details.

Flowcharts

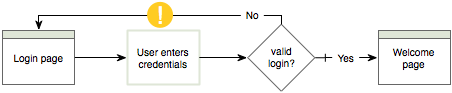

While these are possibly the least appreciated documents among designers, flowcharts [or flow diagrams] tend to rate very highly with the stakeholders and team members that consume them. As designers we sometimes see them as unnecessary because we often have the "big picture" that the flowchart communicates in the back of our heads. Other stakeholders don't tend to have that information at the back of their minds and appreciate the easy communication that flowcharts provide.

This is a wholely unsexy form of documenting, but people understand them and that makes them useful.

Spool cited experiences he's had with flowcharts and raised the question

How do you determine what level of detail to focus on?If you get too focused on the details it takes forever, if you go too high the flow isn't clear.

In my work I tend to put together different flowchart style diagrams for different situations, often a high level flow (more of a site map or application flow diagram) and as needed assembling more specific process flow diagrams that provide more detail.

Brown's comment on designers neglecting this form of diagramming is well taken, in that when I feel time pressure low level process flows are typically the first thing I drop from my process, occasionally to my regret. Perhaps the clarity of communication that flowcharts provide is part of why we neglect it. We look and say "well, duh" and wonder why we took the time, forgetting the power these diagrams have to quickly communicate the flow to other members of the team and to our customers.

Documents as people

You don't want to give people too many responsibilities. You shouldn't assign too many responsibilities to a document either. Like a person they've got their limits of what they can deliver.

Establish a purpose for the document. What am I trying to accomplish? What is this document's role in the design process?

If you have a purpose for the document you can make sure that everything about that document serves the purpose. You can become ruthless in decision making.

I see the ruthless editing this enables as the take-away. Mercilessly slash the cruft that doesn't serve the doc's purpose from your deliverables. Is the level of detail I'm using here accomplishing the objective? No? Readjust.

Having a clear purpose can be more difficult the more stakeholders there are working with the document. As different opinions fly about what a document's purpose is the opportunity to ruthlessly slash closes up.

It's possible for the responsibilities of a document to change over the life cycle. As you reach different points in the project the purpose of a document may change.

I've seen changes over the lifecycle take multiple forms. In some cases I've seen document formats change to address a shift in responsibility, such as wiki delivered annotated wireframes getting additional technical annotations from the Front End team. In others the documents themselves have remained unchanged but they've been put to different purposes than those they originally served. I've seen such changes most frequently in how site maps and high level application flow diagrams have been used by the team and customers over the lifecycle.

User testing your documents

This was an especially interesting question Spool brought up in the interview. We test the software that results from the documents to make sure it meets user needs, are we also testing the documents to make sure they meet user needs?

Brown suggests showing customers past documentation as a sample to get their reaction to it and see if the content and presentation works for them. In a sense it's like doing a competitive evaluation. Here's this sample, get reactions to it and adapt.

Iterative process is another option, taking the documentation to the customer, take comments on format and further improve to match customer needs. (This would hold true as well for internal documentation, something we've done from time to time with our developers and quality analysts.)

I've tended more toward the second option than the first, and done most testing iterations on internal documentation where the cost of entry has typically been very low. Asking questions about document format doesn't tend to make internal folks nervous where some customers take questions about document format as a sign you're making things up as you go. I think Brown's suggestion of how to approach user testing the docs with customers by using old documents does a good job of addressing this potential gotcha.

Books and intervening experience

The interview rounds up with Brown talking about how his thoughts on some of the various deliverables have changed. Some items he considered optional when writing the book are necessary (such as annotations on wireframes) and some things he thought essential he'd now skip over.

As the responsibilities of the various documents he wrote about have shifted, the best practices have shifted as well, making the samples in the book a starting point from which to adapt rather than a template to simply adopt. As always, the designer must take the inputs and decide how to adjust to meet the users' needs.